»Old Vienna Goes American«.

Schnitzler, Playwright and Novelist, Says His Countrymen Have Acquired

All of U. S. Habits Except Energy and

Success

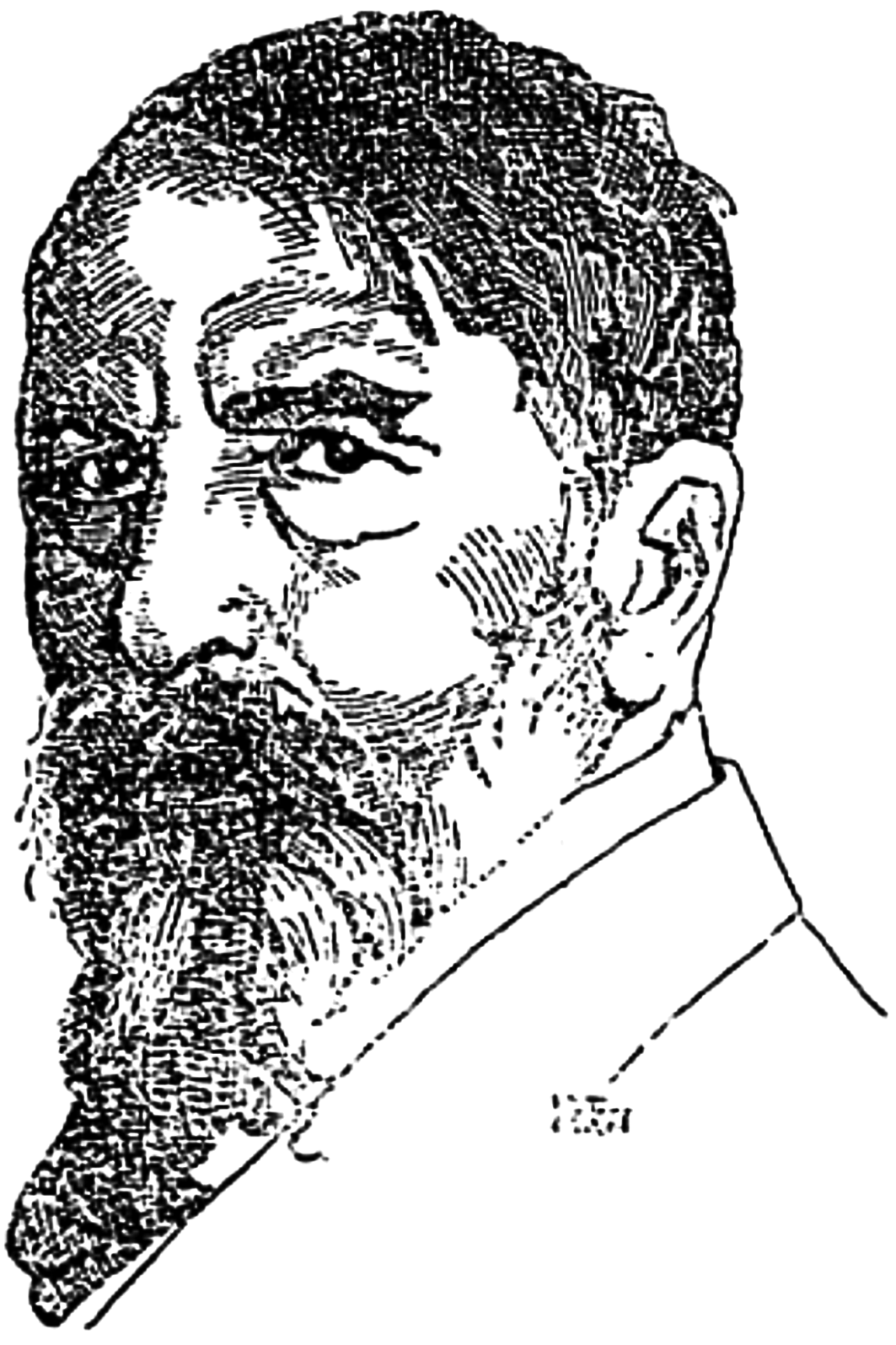

Arthur Schnitzler, Viennese

playwright and novelist, an interview with whom is reported below by Karl

Scheuermann, a Milwaukee newspaper man, is one

of the chief figures in contemporary continental literature. In America, however, he is more widely known for his novels,

many of which have been translated from the German, than he is for his plays.

Among the former are »Fraulein Else,« »Beatrice,« »Rhapsody« and »Therese,« of which

the last named is his longest and was published this fall.

Complications greet the interviewer who would see Arthur Schnitzler, internationally known playwright and novelist, at his

home in Vienna. For Herr Schnitzler, like most famous and much bothered men, is not at

home to everybody and to guard against casual interruptions at his work has a silent

telephone number. Although I have carried on a correspondence with him for a matter

of 15 years or more, it was necessary for me to go through the formality of calling

at his home, Sternwartestrasse 71, inquiring for

his telephone number and then making the telephonic introduction, which he requires,

at an appointed time.

Yes, he would be glad to see me he said – sometime within the next day or two. The

following morning Mr. Schnitzler called to

say he would chat with me for an hour or so at 6 30 that evening.

The thing that struck me about the author of »Anatole,« »Reigen,« »Light o Love,« as he stepped from a room on the second floor of his carefully groomed

villa, was his grayness. A gray beard that had grown beyond the well defined outlines

of a Van Dyke; gray blue eyes below gray brows and squinting lids: a gray mane combed from the right side

of the massive head toward the left ear; a gray blue cutaway that seemed almost too

tight for shoulders chunky rather than broad and indicative of a life at the desk

rather than on football grounds.

I recalled his liking for gray from his letters – his stationery was of that

color. I was reminded at the same time that here was no longer the Schnitzler of the »Anatole« days but a man past 60, careworn and wincing under the reality of

death, the same death with which he has toyed in so many of his plays and novels and

which, a few months ago, took from him his beloved daughter.

Mr Schnitzler did not sit long at a time during

our chat of two hours or so. He likes to stand or move about while he talks and this

is his habit also when he is busy on a new novel or play. Mr Schnitzler stands there speaking with a voice of extremely

musical timbre and with a precision of intonation and liveliness of tempo that bear

no suggestion of the Viennese or Austrian »I should worry« attitude. He agreed with me that

the much talked about geniality and social gracefulness of the Viennese are but surface elements, that the Viennese is spending too much of his time in the coffee house

and that the traditional »Schlamperei« in public offices has grown rather than

decreased in the 10 years that Austria has been

a republic. Holidays are declared on every pretext.

»We seem to have so much time here,« said Schnitzler, »but have we? Compared with Germany we are making slow progress in our reconstruction work. There are

too many officials. It seems people must be employed somehow.«

I have observed that the only time when a Viennese

has no time is when he has to make, or thinks he has to make, an electric train or

street car. He will chase after it for a block and swing onto it with an athletic

experience that is as remarkable as it is suicidal. Now police authorities are

considering energetic steps to stop the nuisance which, clearly visible legends in

all street cars inform you, is strictly prohibited by law.

Mr Schnitzler, by the way, considers railroad

and electric train riding the most dangerous transportation hazards, more so than

a

trans-Atlantic boat trip. He would rather fly than float, and feels himself nowhere

safer than when in an airship.

»I wouldn't mind a trip to America but for the railroad distances. Once in America I would want to see all. New York alone wouldn't do. I have been approached several

times by lecture tour managers but the financial reward offered does not warrant the

effort.«

Which brought the conversation to the chronic emptiness of the Austrian pocketbook and the tremendous influence American financial and industrial supremacy is

having upon all phases of life in Europe

today.

»Anything and everything American is above par,

in the public’s imagination as well as in the realities of the market,« said Schnitzler. »We imitate and adopt American clothes, American music, American plays, American films, American traffic rules, American sports,

American everything except American energy and success.«

Of American plays that are now »packing ’em in«

over here Mr. Schnitzler had in mind »Broadway,« »Chicago,« »An American Tragedy,« »The Trial of Mary Dugan.«

»It is only seldom that I go to a theater,« the writer of world renowned plays

declared. »I would go to concerts in years gone, my natural artistic inclination

being decidedly more toward music than the stage. However, I am a keen frequenter

of

the kino (movie) as it permits one to come and go as one pleases and gives one many

things that are not possible on the stage. I have seen quite a number of American films. There was a time when American pictures were poor, but that time is of

the past.«

There are several persons whom Mr Schnitzler

would like to meet should he come to America. One

is a publisher who, he said, paid him a pittance for the

limited number edition of »Casanova’s

Homecoming,« and the other a New York lawyer whom he had engaged

to prosecute the publisher but from whom he heard nothing after the first exchange

of

courtesies.

Schnitzler by the way, is still a practicing physician, the profession which he

followed exclusively before his success as a dramatist and novelist. Not a few of

his

plays are built around themes which have grown out of his medical experience. At the

literary Burg theater in Vienna his most frequently played

drama is »Der Junge Medardus,« followed by »Das Weite Land« and »Komoedie der Verfuehrung.«